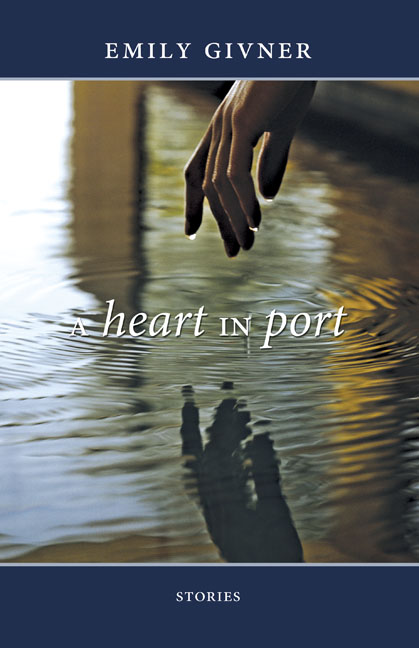

The fictional worlds that Emily Givner was intent on evoking are subtle, yet lucid, her characters often wrought with inherent contradictions, her narrators keen-eyed and pithy. In the title story of the collection, “A Heart In Port”, a seemingly light hearted send up of heartbreak, a Canadian woman waits in vain for the return of her European lover, amid the comedic shards of those close to her. The narrator’s caustic eye shifts between lives touched by illness and disappointment and the backdrop of life’s sharp ironies. Irony is apparent as well in “In-Sook” when a visiting music professor adored by his Korean students finds himself in conversation with the glass eye of one. When the glass eye starts speaking to Professor Andresj, the voice leads him to certain infidelity with the one student who is capable of the encounter. This mode of the surreal also enlightens the Kafkaesque “The Resemblance Between a Violin Case and a Cockroach”, a story which (quite apart from its quiet forewarning of Emily Givner’s own death) is a juggling act of improbability, breakdown, sly rhetoric, fairytale and literary allusion, all sustained by the perceptions of a young girl, Clarissa. These stories are never quite what they present themselves as being.

In some – “Canadian Mint and Private Eye” – a small apparent flaw in the story’s internal logic creates a puzzle and a hint and, to solve that puzzle, the reader is led back to the story again to read it with new eyes. There is often something otherworldly afoot – too organic to be merely surreal, too witty to strain credulity.

Always pealing the layers of intense relationships, Givner never lets questions of culture, race and politics escape her. In “Polonaise” the relationship between an older Polish musician and young Canadian Jewish woman is consummated under the cloud that anti-Semitism is alive and well in Poland.